Fluid Mechanics Derivations

Minor Loss Equation

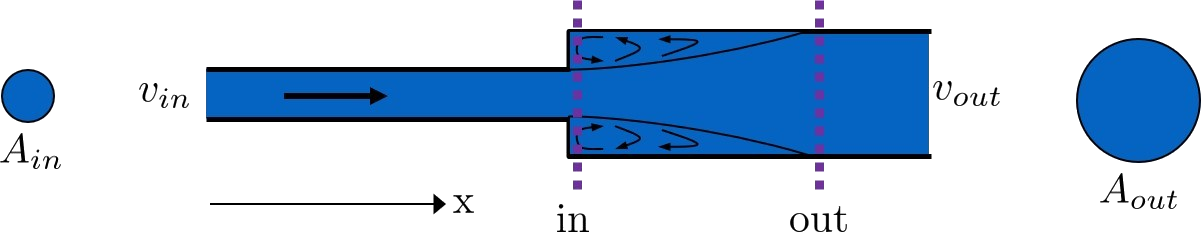

This section contains the derivation of the minor loss equation using the following figure as a reference. The derivation begins with a slightly simplified energy equation across the control volume shown. Our energy equation begins with \(h_P\) and \(h_T\) having been eliminated.

Fig. 25 This is the system we will use to derive the minor loss equation.

Since the elevations at the center of the \(in\) and \(out\) control surfaces are the same, we can eliminate \(z_{in}\) and \(z_{out}\). As we are considering such a small length of pipe, we will neglect the major loss component of head loss. Thus, \(h_L = h_e + \cancel{h_f}\). The following three equations are all the same, simply rearranged to solve for \(h_e\).

This last equation has \(h_e\) as a function of four variables \((p_{in}, \, p_{out}, \, v_{in}\), and \(v_{out})\); we would like it to be a function of only one. Thus, we will invoke conservation of momentum in the horizontal direction across our control volume to remove variables. The difference in momentum from the \(in\) point to the \(out\) point is driven by the pressure difference between each end of the control volume. We will be considering the pressure at the centroid of our control surfaces, and we will neglect shear along the pipe walls. After these assumptions, our momentum equation becomes the following:

Recall that momentum is mass times velocity for solids, \(m v\), with units of \(\frac{[M][L]}{[T]}\). Since we consider water flowing through a pipe, there is not one singular mass or one singular velocity. Instead, there is a mass flow rate, or a mass per time indicated by \(\dot m = \rho Q\), which has units of \(\frac{[M]}{[T]}\). Therefore, the momentum for a fluid is \(\rho Q \bar v\). Applying the continuity Equation \(Q = \bar v A\), we get to the following equation for the momentum of a fluid flowing through a pipe which we will use in this derivation, \(M = \rho \bar v^2 A\). The pressure force is simply the pressure at the centroid of the flow multiplied by the area the pressure is acting upon, \(p A\).

To ensure correct sign convention, we will make each side of the equation negative for reasons discussed shortly. Since \(\bar v_{in} > \bar v_{out}\), the left hand side will be \(M_{out} - M_{in}\) in order to be negative. The reduction in velocity from \(in\) to \(out\) causes an increase in pressure, therefore \(p_{in} - p_{out}\) is negative. With these substitutions, the conservation of momentum equation becomes as follows:

Note that the area term attached to \(p_{in}\) is actually \(A_{out}\) instead of \(A_{in}\), as one might think. This is because \(A_{out} = A_{in}\). We chose our control volume to start a few millimeters into the larger pipe, which means that the cross-sectional area does not change over the course of the control volume.

Dividing both sides of the equation by \(A_{out} \rho g\), we obtain the following equation, which contains the very same pressure term as our adjusted energy equation above, Equation (16). This is why we chose a negative sign convention.

Now, we combine the momentum, continuity, and adjusted energy equations:

To obtain an equation for minor losses with just two variables, \(\bar v_{in}\) and \(\bar v_{out}\).

Now we will combine the two terms. The numerator and denominator of the first term, \(\frac{\bar v_{out}^2 - \bar v_{in}^2\frac{\bar v_{out}}{\bar v_{in}}}{g}\) will be multiplied by \(2\) to become \(\frac{2 \bar v_{out}^2 - 2 \bar v_{in}^2\frac{\bar v_{out}}{\bar v_{in}}}{2 g}\). The equation then looks like:

Final Forms of the Minor Loss Equation

Factoring the numerator yields to the first ‘final’ form of the minor loss equation:

From here, the two other forms of the minor loss equation can be derived by solving for either \(\bar v_{in}\) or \(\bar v_{out}\) using the ubiquitous continuity Equation \(\bar v_{in} A_{in} = \bar v_{out} A_{out}\):

You will often see \(K_e^{'}\) and \(K_e\) used without the \(e\) subscript, they will appear as \(K^{'}\) and \(K\).

Being familiar with these three forms and how they are used will be of great help throughout the class. The third form is the one that is most commonly used.

We can convert the minor loss coefficient, \(K_e\), into a flow contraction using the minor loss equation (see Equation (17))

where \(\Pi_{vc}\) is the ratio of the contracted area to the full expanded flow area.

Given that \(\Pi_{vc}\) is the ratio of the contracted area to the full expanded flow area we obtain the relationship between the contracted diameter, \(D_{vc}\), and the expanded diameter, \(D_{pipe}\).

Solving Equation (18) for \(\Pi_{vc}\) we obtain

The extent of a flow contraction, \(\Pi_{vc}\) can be estimated from the measured minor loss coefficient.