Rapid Mix Theory and Future Work

Our understanding of the coagulant nanoparticle attachment to suspended particles and dissolved species is currently quite speculative. This is an area that requires substantial research and modeling because it has the potential to significantly influence the design of flocculators. We have anecdotal evidence that the process of transporting coagulant nanoparticles to suspended particle surfaces may be a slow, rate-limiting process, especially when coupled with high rate flocculators. Dissolved organic matter may slow the rate of coagulant nanoparticle transport by effectively increasing the size of the coagulant nanoparticles and thus reducing the diffusion rate.

Developing a fundamental understanding of the mixing and transport processes that occur between coagulant addition and flocculation is a very high priority for the AguaClara program.

Diffusion and Shear Transport Coagulant Nanoparticles to Clay

The time required for shear and diffusion to transport coagulant nanoparticles to clay has previously been assumed to be a rapid process.

Our analysis suggests that this critical step may require significant time especially given our effort to reduce the time allotted for flocculation.

Turbulent eddies, viscous shear, and diffusion blends the coagulant with the raw water sufficiently (in a few seconds) so that the coagulant precipitates and forms nanoparticles.

Dissolved organic molecules diffuse to the coagulant nanoparticles and adhere to the nanoparticle surface.

The coagulant nanoparticles are transported to suspended particle surfaces by a combination of diffusion and fluid shear.

The following is a very preliminary estimate of the time required for attachment of the nanoparticles to the clay particles. This analysis includes multiple simplifying assumptions and there is a reasonable possibility that some of those assumptions are wrong. However, the core assumption that coagulant nanoparticles are transported to clay particles by a combination of fluid deformation (shear) and molecular diffusion is reasonable.

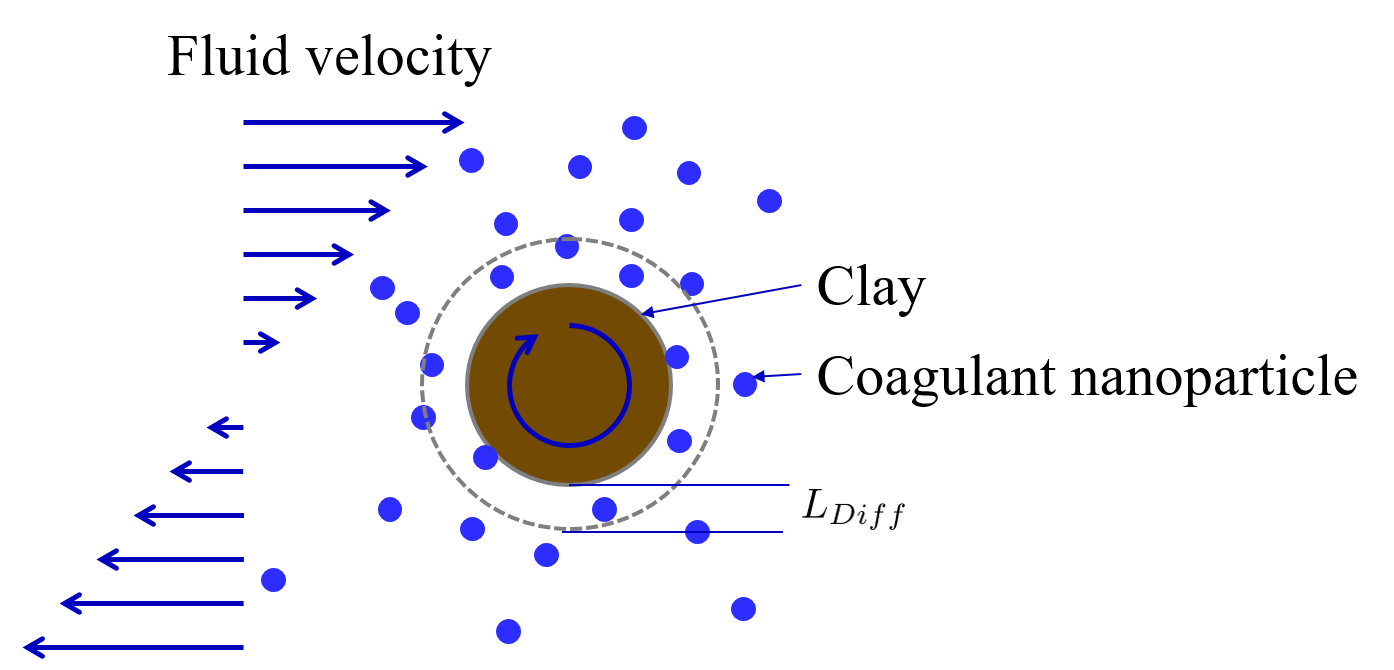

The following analysis is similar to the collision analysis that was developed in the AguaClara flocculation model. The core idea is that viscous shear dominated fluid deformation causes relative motion between the coagulant nanoparticles and the clay particles (or other suspended particles) with which they eventually will collide. The collision between these particles that are very different in size is difficult to achieve because there is a viscous layer of fluid around the clay particles that the clay particles drag with them as they rotate in deforming fluid. Diffusion helps transport the coagulant nanoparticles through this viscous layer.

The volume of the suspension that is cleared of nanoparticles is proportional to a collision area defined by a ring around the clay particles with width of the diameter of the nanoparticle diffusion band. This diffusion band is the length scale over which diffusion is able to transport coagulant particles to the clay surface during the time that the nanoparticles are sliding past the clay particles.

If we go backwards in time, the ring of fluid around the clay particles would deform into two separate highly distorted volumes of fluid, one located to the left of the clay particle and one to the right (see figure Fig. 89). This volume of fluid is assumed to receive nanoparticles that are transported in by fluid deformation.

Fig. 89 Fluid deformation moves coagulant nanoparticles close to clay particles and diffusion helps transport the nanoparticles the last nanometers toward a successful collision.

The time required for shear to transport all of the fluid past the clay so that diffusion can transport the coagulant nanoparticles to the clay surface is significant. The diffusion coefficient for coagulant nanoparticles is given by

where \(d_{cn}\) is the diameter of the coagulant nanoparticles. The length scale over which diffusion is occurring can be estimate from the diffusion coefficient and the time allotted.

The time for coagulant nanoparticles to diffuse through the boundary layer around the clay particles is equal to the distance they travel around the clay particles divided by their velocity. The distance they travel scales with \(d_{Clay}\) and their average velocity scales with the thickness of the diffusion layer/2 * the velocity gradient.

We can eliminate the diffusion time in Equation (158) using Equation (159).

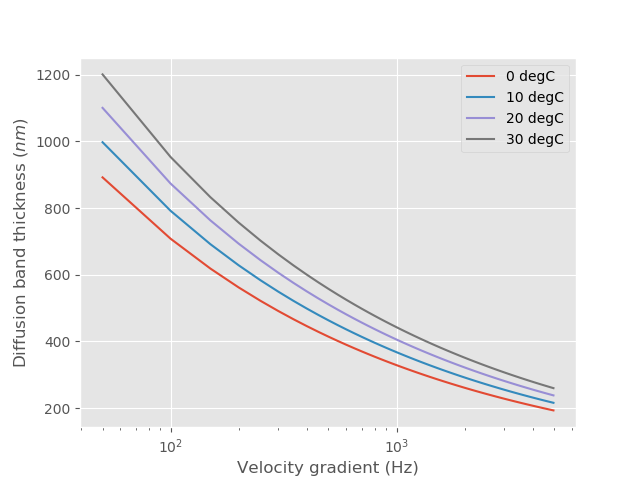

This diffusion layer thickness is the length scale over which diffusion becomes the dominant transport mechanism for coagulant nanoparticles. Let’s estimate the diffusion layer thickness.

Fig. 90 Molecular diffusion band thickness as a function of velocity gradient. This length scale marks the transition between transport by fluid deformation and by diffusion.

Diffusion transports the coagulant nanoparticles a relatively short distance, a fraction of a \(\mu m\).

We need to calculate the rate at which coagulant nanoparticles attach to the clay particles. The long range transport is assumed to be the rate limiting step. The volume cleared is proportional to the area of this ring with the ring thickness equal to the molecular diffusion band thickness. Here we assume that the \(L_{Diff_{CN}} << d_{Clay}\)

The volume cleared is proportional to time.

The volume cleared is proportional to the relative velocity between clay and nanoparticles. This relative velocity is in the viscous layer of fluid in the ring surrounding the clay particle.

We use dimensional analysis to get a relative velocity for the long range transport controlled by shear. The relative velocity between coagulant nanoparticles and the clay particles that they will eventually collide with is assumed to be proportional to the average distance between clay particles. This assumption is both critical for the following derivation and is suspect. It is critical because if we were to assume that the relative velocity caused by shear is proportional to the nanoparticle diameter, the clay diameter, or the diffusion length scale, then the velocity would be extremely small and the time to clear the volume of fluid associated with one clay particle would take a very long time. However, wishing for a speedy process doesn’t justify incorrect scaling. The relative velocity is assumed to be the velocity at which coagulant nanoparticles are transported into the two separate fluid volumes that will deform into the ring around the clay particles in the next few seconds.

The assumption that the relative velocity scales with the average distance between clay particles leads to the following steps. The first step is just a proposed functional relationship. We could also have jumped to the assumption that the relative velocity is a function of the length scale and the velocity gradient.

In a uniform shear environment the velocity gradient is linear. Thus the relative velocity must be proportional to the length scale.

The only way to for \(\varepsilon\) and \(\nu\) to produce dimensions of time is to combine them to create 1/G.

Combining the three equations for \({\forall_{\rm{Cleared}}}\) and the equation for \(v_r\) we obtain the volume cleared as a function of time.

Collision Rates and Particle Removal

The time for all of the fluid to have had one opportunity for a collision occurs when:

The successful collision rate (the attachment rate) is given by:

Substitute the equation for \(t_c\).

A fraction of the remaining coagulant nanoparticles are removed during the time required for one sweep past the clay particles.

Integrate from the initial coagulant nanoparticle concentration to the concentration at time t.

Use pC notation to be consistent with how we describe removal efficiency of other contaminants.

Solve for the time required to reach a target efficiency of application of coagulant nanoparticles to clay.

If we assume that we are willing to invest a certain amount of energy in the process, then we can estimate the time required to achieve a target coagulant nanoparticle application efficiency. The velocity gradient in the reactor where the coagulant is attaching to the clay particles is related to the head loss or drop in water level, \(\Delta h\), through the reactor.

Replace \(\theta\) with \(t_{coagulant, \, application}\).

Solve for the velocity gradient.

Using the equation for \(L_{Diff}\) above, we can solve for the time required to reach a target efficiency of application of coagulant nanoparticles to clay:

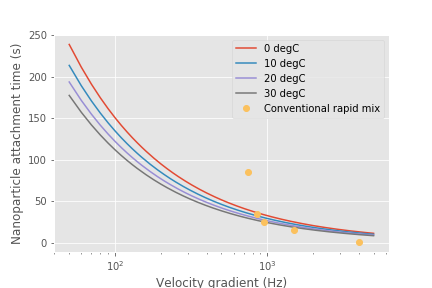

The time required for the coagulant to be transported to clay surfaces is strongly dependent on the turbidity as indicated by the average spacing of clay particles, \(\Lambda_{Clay}\). As turbidity increases the spacing between clay particles decreases and the time required for shear to transport coagulant nanoparticles to the clay decreases. Increasing the shear also results in faster transport of the coagulant nanoparticles to clay surfaces. The times required are strongly influenced by the size of the coagulant nanoparticles because larger nanoparticles diffuse more slowly.

Fig. 91 An estimate of the time required for 80% of the coagulant nanoparticles to attach to clay particles given a raw water turbidity of 10 NTU.

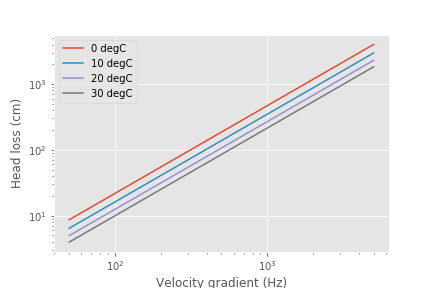

Energy Tradeoff for Coagulant Transport

This code shows how the following plot can be generated

Fig. 92 The total energy required to attach coagulant nanoparticles to raw water inorganic particles increases rapidly with the velocity gradient used in the rapid mix process.

There is an economic tradeoff between reactor volume and energy input. The reactor volume results in a higher capital cost and the energy input requires both higher operating costs and higher capital costs. This provides an opportunity to optimize rapid mix design once we have a confirmed model characterizing the process.

The total potential energy used to operate an AguaClara plant is approximately 2 m. This represents the difference in elevation between where the raw water enters the plant and where the filtered water exits the plant. If we assume that the rapid mix energy budget is a fraction of that total and thus for subsequent analysis we will assume somewhat arbitrarily that the energy available to attach the coagulant nanoparticles to the raw water particles is 50 cm.

We solve the coagulant transport model, \(t_{coagulant, \, application} = \frac{2.3p C_{CN} \, \Lambda_{Clay}^2}{\pi G k \, d_{Clay}\, L_{Diff_{CN}} }\), for G given a head loss.

The maximum velocity gradient that can be used to achieve 80% coagulant nanoparticle attachment using 50 cm of head loss is 283 Hz. This requires a residence time of 61 seconds. These model results must be experimentally verified and it is very likely that the model will need to be modified.

The analysis of the time required for shear and diffusion to transport the coagulant nanoparticles the last few millimeters suggests that it is the last step of diffusion to the clay particles that requires the most time. Indeed, the time required for coagulant nanoparticle attachment to raw water particles is comparable to the time that will be required for the next step in the process, flocculation.

Coagulant Attachment Mechanism

We do not yet understand the origin of the bonds that form between coagulant nanoparticles, between a coagulant nanoparticle and a suspended particle, and between coagulant nanoparticles and dissolved organic molecules. Historically the role of the coagulant was assumed to be to reduce the repulsive force between particles so that the particles could get close enough for Van der Waals forces to hold the particles together. That neglected the fact that Van der Waals forces were already acting between the water molecules and the suspended particle surfaces. In order for the water molecules to be pushed out of the way it is necessary for the coagulant nanoparticles to have stronger bonds with the suspended particles than the bonds between water molecules and the suspended particles.

The water molecules are subject to Brownian motion and thus it is possible that they are frequently vibrated free from the Van der Waals attractive forces. The coagulant nanoparticles are much larger, less affected by Brownian motion, and thus less likely to be vibrated. The fractal nature of the coagulant nanoparticles may also make it possible for multiple well aligned connections between the two surfaces. The fractal tentacles of the coagulant nanoparticle can align as needed to enable many strong bonding connections to the clay surface.