The Physics of Water Treatment Design

A Different Kind of Textbook

This textbook represents our cumulative insights from our journey that has been motivated by a quest to make the world a better place where everyone has access to safe water on tap, the engineering challenge of optimizing the design of drinking water treatment plants, and the curiosity to understand what controls their performance. We would like to understand what determines which contaminants make it the whole way through a water treatment plant. If we could understand what allows some contaminants to sneak the whole way through a water treatment plant, then we suspect that we could create better designs to more effectively remove contaminants.

Engineering textbooks provide a venue for authors to share what they’ve learned, to organize ideas, and to provide a guide for engineers as they design solutions for real world problems. Engineering textbooks are often intended to document the established core of knowledge. It seems reasonable to assume that what is in textbooks and in peer reviewed literature is mostly true.

The Edge of Knowledge

The assumption that what is written and passed down in oral history through the scientific community is true can lead to missed opportunities and lost insights. The hypotheses from one generation of scientists can too easily evolve into new theories in the next generation and then into established theories for the next. The history of drinking water treatment science is cloudy (think high turbidity!) with hypotheses that miss or misrepresent key concepts.

You might wonder why we care so much about getting the science right and being as clear as possible about what is known. After all, the core drinking water treatment technologies were invented before we were born and many of us have safe drinking water coming from our taps. Environmental Engineers have known how to design municipal drinking water treatment plants since they early 1900’s. We care about getting the science right because we hypothesize that there are many opportunities to significantly improve drinking water treatment technologies and that improved understandings of each unit process have the potential to lead to new breakthroughs.

Our contention is that no one has ever optimized the design of a drinking water treatment plant! We are reasonably certain of this because we don’t yet have models (with equations) that describe performance of most of the core unit processes (rapid mix, flocculation, floc filters, plate settlers, sand filtration) used for surface water treatment. The only possible exception is plate settlers which can be characterized if we know the size and density distribution of the particles.

Traditional drinking water treatment textbooks can too easily miss the opportunity to advance the science of drinking water treatment technologies by presenting certainty where there should be skepticism. For example, rapid mix is described as process that occurs in a few seconds, flocculation is described as a process that should be fastest for high turbidity waters and slowest for low turbidity waters, and filtration performance is described by a model that predicts first order removal with respect to filter bed depth. We will demonstrate why each of these assumptions doesn’t match observations, we will discuss new insights into these processes, and we will identify high priority research questions that have the potential to lead to major improvements in drinking water treatment.

We want to encourage skepticism and we want to develop insights to guide thoughtful skepticism. A key skill for successful engineering is the ability to identify the location of the edge of knowledge. The ability to distinguish between what is reasonably certain and what is still in question is what powers the scientific method of slowly extending knowledge. New insights are difficult to obtain if the research is based on a faulty premise.

Fig. 1 We’ve learned that we can find the edge of knowledge very soon after we begin researching a water treatment technology (artwork created by Yi Wen Ng in 2012).

There are significant knowledge gaps in every process that we cover in this textbook. We aren’t yet able to optimize surface water treatment processes because we don’t yet understand the fundamental physics of many of the processes. We are getting closer, join us on the journey.

We need the brightest and the best to create new and better solutions so we can meet the goal of providing everyone with safe drinking water. This challenge is apparently more difficult than building a space station, designing a fuel cell, or inventing the world wide web. So let’s roll up our sleeves and begin.

Don’t believe everything we say. Ask lots of questions:

How do you know that? The goal here is to identify the difference between what is known and what is hypothesized.

What is the equation that describes the physics of this process? If there isn’t an equation that describes the process and that can be used to design the reactor for the process, then it is likely that the physics of the process is not yet understood.

How could we improve this process? If the physics of a process are fully understood, then dimensionally correct equations can be used to obtain the optimal design for that process.

Is the process design based on “rules of thumb” or on physics? “Rules of thumb” or empirical design guidelines often can be identified by the use of physical parameters that have units. For example, if the design guideline specifies a length, time, or velocity then it is likely that the guideline is not based on physics. If the design guidelines are based on a dimensionless parameter then it is possible that it is based on physics.

Evaluate the data to see if it matches predictions of the hypothesized model. Assess whether the authors acknowledge when their data doesn’t match hypothesized models.

Beware of the use of words that are poorly defined and that hide uncertainty. For example, creating a name for a supposed mechanism to describe all of the observations that don’t fit with your theory does NOT mean that you understand that mechanism. The ability to name something doesn’t mean it is understood (see “sweep” flocculation as an example).

Does this “theory” provide insights that have led to new discoveries or new applications?

Does the “theory” include equations that are based on the fundamental laws of nature?

Does the “theory” use dimensionless constants that are close to one?

Is it an elegant “theory” with no need for special cases?

Uncertainty in Science and Engineering

A challenge for authors is to recognize the difference between what is known with a reasonably high degree of certainty and what is assumed to be true without a solid basis. We struggle to tell the difference between fact and hypothesis. The time-honored approach in science is to rely on the peer review process. That process for vetting knowledge has been shown to be flawed.

Your question could be whether the distinction between fact and hypothesis really matters. If the hypothesis is widely accepted as fact and if it has been accepted for decades what benefit is there to calling it a hypothesis rather than a fact?

This question is at the core of our educational philosophy. Is this text the repository of knowledge that we are providing for you to drink or is this text a conversation where we invite you to join the effort to discover better ways to provide safe water on tap?

Core Principles of AguaClara Innovation

The AguaClara network of organizations has been methodically inventing improved water treatment technologies since 2005. Our success is based on respect, empathy and love. Innovation requires flocculation of ideas. The transport of ideas between organizations and individuals is mediated by respect. Respect as a cornerstone of organizational culture foster rapid and honest exchange of ideas. The rapid pace of innovation in the AguaClara network is sustained thru a shared culture of respect, empathy, and love.

Curiosity can flourish in a culture of love, respect, and empathy. Asking why and why not and pondering an ever growing number of questions has empowered student teams to take on the quest for new knowledge and new solutions.

Any large organization will require a leadership hierarchy and any hierarchy will rely on respect based on fear or respect based on love. Fear-based hierarchies impede the accurate sharing of information and can easily devolve into data-free and low-truth decision-making schemes. According to Liz Ryan, the characteristics of fear-based leaders include:

They’ll Teach You, Whether You Like It or Not

Everyone is a Friend or a Foe

It’s All about the Trophies

They Don’t Step Outside Boxes

They’re Addicted to Yardsticks

Love-based hierarchies foster honesty and a free-flow of information. Reflection is encouraged across the organization and truth, honesty, and integrity are valued. Staff at the bottom of the hierarchy know that their opinions and reflections are valued and thus they will be willing to report problems to organization leaders and share their ideas.

Love-based leaders relate to others based on true respect for the other. They will take the time to converse with people at all levels of the organization and will value the opportunity to speak with people who are the interface between the organization and the rest of the world. A person’s value is based on being a person, not based on position in the hierarchy.

As water treatment plant designers it is critical that we spend time with a diverse set of stakeholders including community members and water treatment plant operators. Those relationships must begin with respect and valuing their insights. As we spend time together we can develop trust so that they communicate both the good and bad.

We’ve learned much from plant operators. They figured out how to reduce rising flocs at Agalteca, Honduras where we learned that conventional clarifier inlet manifolds generate large circulation currents. Plant operators added curtains to the windows at Moroceli, Honduras (see Fig. 2) because they noticed that direct sunlight on the clarifiers caused an increase in settled water turbidity.

Fig. 2 Moroceli AguaClara water treatment plant operators installed curtains to reduce direct sunshine on clarifiers. Solar heating produces density currents that carry flocs to the top of the clarifier.

Empathy is fundamental in design. Empathy enables us to consider reality from another’s perspective. Empathy enables us to bring the people who will use or benefit from a technology into the design considerations. Empathy brings the insight that water treatment plants need to have roofs and provide a secure work environment both day and night. Empathy brings the insight that replacement parts must be readily available and that generic components are preferred over specialty proprietary components.

The Global Context for Drinking Water Treatment

The Sustainable Development Goals: SDGs and specifically SDG 6 provide the context and motivation for this text. The first SDG 6 target is: “By 2030, achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all.” That goal is daunting and won’t be met using the approaches of the past 5 decades. This text is about creating a new paradigm for the design of high performing water treatment technologies with the goal of making a real contribution toward SDG 6.1.

Fig. 3 Sustainable development goal 6 is all about clean water and sanitation.

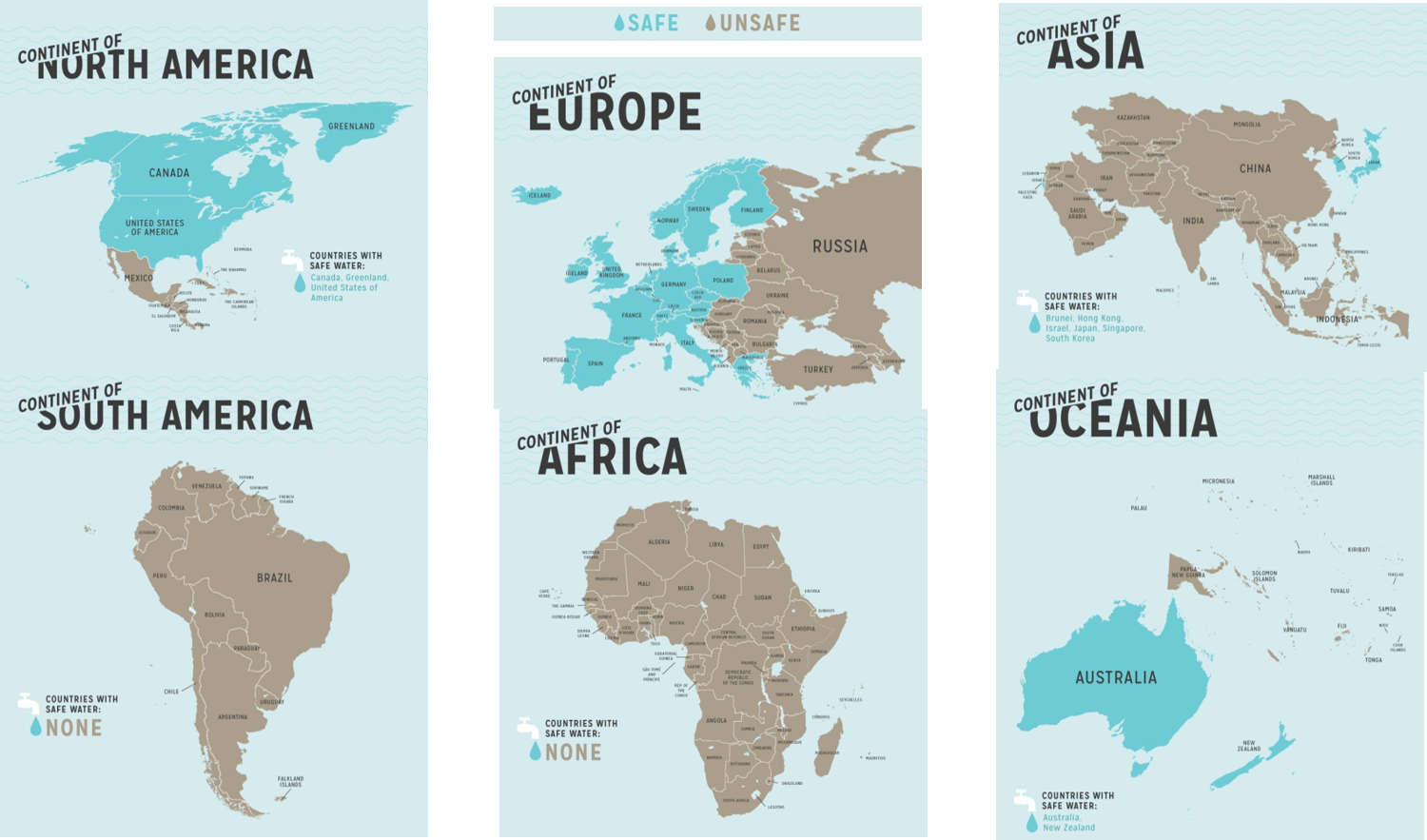

The number of people who currently lack access to reliable safe water on tap is not known. Estimates range from “1.8 billion who use a source of drinking water that is contaminated with feces” to the Centers for Disease Control recommendations for where it is usually safe to drink tap water.

Fig. 4 There are relatively few countries where it is almost always safe to drink the tap water.

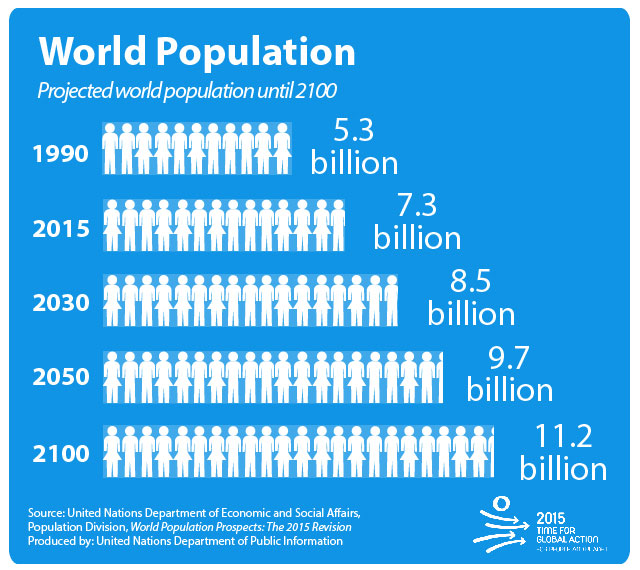

Fig. 5 1.2 billion people will be added to the global population between 2015 and 2030.

Thus by 2030 we need to provide safe water for at least 3.3 billion people AND maintain the water supply systems for the 5.2 billion who currently have access to safe water. That is a daunting number that requires some exploration!

Use this code to calculate the increased capacity

If we provide 260 L/day per person, then we need to provide the equivalent of 19 water supplies for New York City every year between now and 2030. The planet needs approximately 800,000 L/s of new capacity each year. AguaClara water treatment plants cost approximately $10,000 per L/s of treatment capacity. Thus the budget for global water treatment needs to be 8 billion USD per year. Note that this doesn’t include any other aspects of supplying water. Managing water sources, transmission lines, storage, and distribution systems are even more expensive than water treatment.

The need for drinking water supplies isn’t limited to the global south. The California Urban Water Agencies estimate that 530,000 or more people in rural areas of California are unable to turn on their tap and access clean, safe water.

Safe Water Access

The simple answer is that they are too poor and are unable to afford safe water on tap. But it isn’t that simple! Families without access to safe water on tap often spend more for water than families with safe water on tap. There seem to be two key reasons why those with limited financial resources often have limited access to water, poor quality water, and yet pay a premium for that water.

The first reason for the lack of safe water has been the poor track record of water treatment infrastructure. The frequent failures and high operating costs of municipal scale water treatment systems have led many decision makers to conclude water treatment infrastructure isn’t a worthwhile investment. Politicians who invest political capital to bring water treatment to their community often find that after the initial ribbon cutting there is little political benefit because the system doesn’t deliver the benefits to the community that they had promised.

The second reason for the lack of safe water is the lack of access to capital for municipal scale infrastructure. Even though an AguaClara water treatment plant would pay for itself in a fraction of its useful life, there is not yet a financial mechanisms for communities to access a loan so that they can make the investment. A community would need to save enough money to be able to purchase a water treatment plant (as was the case for Las Vegas, Honduras), a bilateral donor can finance a plant through a donation, or the national government can use sovereign debt or taxes to finance plants. The challenge for a community is to obtain the financial or political power to access the needed funds.

As we work to solve a global challenge that has been plaguing humanity since the dawn of human civilization, then it will serve us well to understand a bit of the history that has led to our current reality. Water treatment history includes amazing successes, persistent failures, fortuitous discoveries, a heavy reliance on empiricism, and an occasional myth. Our goal is learn from and reflect on our history and then create even better solutions.

Introduction to Surface Water Treatment

We treat water because it doesn’t meet the requirements for its intended use. We need to understand the problem so that we can understand existing and novel water treatment technologies.

Water Contaminants

Many substances are able to dissolve in water. Additionally, water is able to carry suspended solids because of its high density. The substances may be naturally occurring, anthropogenic, benign, or harmful. The types of contaminants are influenced by the water source. Contaminant concentrations are often highly variable over time.

A water treatment system must be able to handle the likely range of contaminant levels and produce treated water that meets the user requirements. In some cases the user may have the option of switching sources or reducing demand when a source becomes excessively contaminated for a limited period of time. For example, a municipal water supplier may be able to shut the plant down for a few hours to avoid having to treat a very dirty water after a rainstorm. This strategy can work well for water sources that have small watersheds and hence a rapid return to better water after the storm passes. In other cases the water treatment processes must be capable of treating the most contaminated water that the water source provides. In any case, selecting the best unit processes to treat a given water source for a particular use case can be challenging. It is common to find water treatment plants that are unable to adequately treat their water source.

Particles

Surface waters (rivers, streams, lakes) and some ground water (especially ground water under the influence of surface water) inevitably carry some suspended particles. “Particles transported by rivers are composed of resistant primary minerals (e.g., quartz and zircon), secondary minerals (clays, metallic oxides and oxyhydroxides) and biogenic remains.” Many of these particles may be harmless, but there is good reason to be hesitant to drink water with a high concentration of suspended particles.

Pathogens

Pathogens include viruses (100 nm), bacteria (1 \(\mu m\)), and protozoa (several \(\mu m\)). Pathogens are particles and are removed by processes that remove particles along with other microbes, organic and inorganic particles.

Turbidity

Turbidity or cloudiness is an indirect measure of particle concentration. Turbidity is an optical measurement of scattered light. Light scattering by refraction is primarily caused by particles that are smaller than but close to the wavelength of light. Particles that are close to but larger than the wavelength of light can reflect light. Turbidity measures both of these effects by shining a light into a water sample and then measuring the scattered light with a photodetector at 90°. The meter is then calibrated with standard suspensions.

For a given suspension the turbidity can be directly correlated with the suspended solids concentration. However, that relationship is complicated because the amount of scattered light is related to the particle size distribution because given the same mass concentration, smaller particles have more surface area and thus reflect more light.

Although turbidity would seem to be an odd parameter to use to measure water quality, it turns out to be the most widely used water quality measurement. The reasons are simple. First, turbidity is amazingly easy to measure over a very wide range of particle concentrations (perhaps 10 \(\mu g/L\) to 1 \(g/L\)). The test doesn’t require any reagents and it can be done in a flow through sample cell for real time measurements. Second, particle free water is pathogen free water. Third, disinfection processes (chlorination, ozonation, UV light) are all significantly less effective at inactivating pathogens if there are other particles present in the water.

Dissolved Species

The list of dissolved species that can be present in water in the environment is endless and ranges from natural organic matter (from decay of plants) to caffeine to atrazine. Usually the highest concentration class of molecules is dissolved natural organic matter (NOM). NOM has some similarity to inorganic particles in that it isn’t necessarily harmful and yet there are several reasons why removal of NOM is an important water treatment goal.

From an aesthetic perspective, NOM absorbs light at short wavelengths and this results in water that looks yellow or brown. While I enjoy drinking tea with a rich brown color, I’d prefer that my water be clear.

NOM plays a supersized role in influencing performance of surface water treatment plants. NOM has three negative effects:

It requires higher dosages of coagulant for effective particle removal.

It reduces the disinfection effectiveness of chlorine, ozone, and UV. Chlorine partially oxidizes the NOM and thus more chlorine must be used to maintain a residual level of chlorine.

It can produce disinfection by-products that are toxic.

Thus removal of NOM is a water treatment goal. Fortunately the same coagulants that are used for particle removal also can remove a significant fraction of NOM. The interactions between NOM and coagulants will be discussed in the Introduction to Rapid Mix.

The removal of other dissolved species is beyond the scope of the first release of this textbook. The authors intend to add sections on the removal of some dissolved species in the near future.

Chlorination

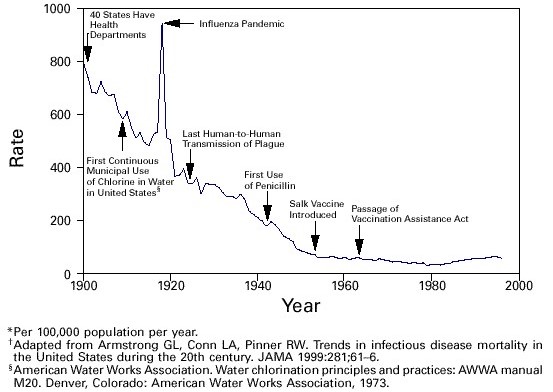

Chlorine is widely recognized for reducing mortality from water borne disease in the United States. A more careful review of the mortality data and of the ability of chlorine to inactive various pathogens makes it difficult to assess the role of chlorine. A classic graph (see Fig. 6) has been used to suggest that chlorination of drinking water supplies resulted in a significant reduction in mortality

Fig. 6 Classic graph showing the reduction in the death rate for the United States from 1900 to 1996.

Treatment Trains

Technology |

Description |

Prerequisite |

Owner |

Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Simple sedimentation |

particles settle |

none |

public |

unknown |

Flocculation |

aluminum and iron salts |

none |

public |

|

Clarification |

horizontal flow |

flocculation |

public |

unknown |

Lamellar sedimentation |

plate or tube settlers |

flocculation or floc filter |

public |

|

Roughing filter |

simple sedimentation in a gravel bed |

none |

public |

|

Slow sand filtration |

Roughing filter or single step treatment for low NTU water |

none |

public |

|

Rapid sand filtration |

depth filtration |

sedimentation |

public |

|

Stacked rapid sand filter |

gravity powered backwash |

lamellar sedimentation |

AguaClara Cornell open source |

|

Floc filter |

upflow fluidized suspension of flocs |

flocculation |

public |

|

Jet reverser floc filter |

first fully fluidized floc filter |

flocculation |

AguaClara Cornell open source |

|

Ballasted sedimentation |

micro sand increases floc density |

|||

Superpulsator |

pulsing flow through floc filter |

rapid mix |

||

Dissolved air flotation |

bubbles carry particles upward |

flocculation |

Public |

The prerequisites for the unit processes in Table 2 reveal that surface water treatment almost always requires a series of treatment steps. A treatment train is a series of treatment steps (or unit processes) designed to convert a contaminated source water into a purified water meeting the use requirements.

- Example treatment trains include:

Conventional mechanized treatment: mechanical flocculation, lamellar sedimentation, rapid sand filtration, disinfection

Superpulsator: rapid mix, floc filter, lamellar sedimentation, rapid sand filtration

AguaClara: hydraulic flocculation, floc filter, lamellar sedimentation, stacked rapid sand filtration, disinfection

Membrane filtration: flocculation, sedimentation, rapid sand filtration, granular or powdered activated carbon, pre-oxidation (see Review Article)

The AguaClara Treatment Train

Why does flocculation precede sedimentation? Which process removes the largest quantity of contaminants?

Sedimentation is the process of particles ‘falling’ because they have a higher density than the water, and its governing equation is:

The code to generate a plot that shows this relationship can be found here

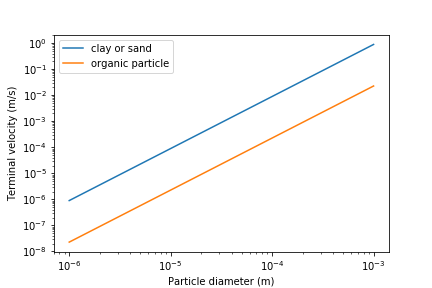

The terminal velocities of particles in surface waters range over many orders of magnitude especially if you consider that mountain streams can carry large rocks. But removing rocks from water is easily accomplished, gravity will take care of it for us. Gravity is such a great force for separation of particles from water that we would like to use it to remove small particles too. Unfortunately, gravity becomes rather ineffective at separating pathogens and small inorganic particles such as clay. The terminal velocities ((1)) of these particles is given in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7 The terminal velocity of a 1 \(\mu m\) bacteria cell is approximately 20 nanometers per second. The terminal velocity of a 5 \(\mu m\) clay particles is 30 \(\mu m/s\). The velocity estimates for the faster settling particles may be too slow because those particles are transitioning to turbulent flow.

The low terminal velocities of particles that we need to remove from surface waters reveals that sedimentation alone will not work. The time required for a small particle to settle even a few mm would require excessively large clarifiers. This is why flocculation, the process of sticking particles together so that they can attain higher terminal velocities, is perhaps the most important unit process in surface water treatment plants.

- The AguaClara treatment train consists of the following processes

flow measurement

metering of the coagulant that will cause particles to stick together

mixing of the coagulant with the raw water

flocculation where the water is deformed to cause particle collisions

floc filter where large flocs settle through water that is flowing upward causing collisions between small particles carried by the upward flowing water and the large flocs

plate settlers (lamellar sedimentation) where gravity causes particles to settle to an inclined plate and then slide back down into the floc filter

stacked rapid sand filtration where particles collide with previously deposited particles in a sand filter bed

disinfection with chlorine to inactivate any pathogens that escaped the previous unit processes

Comparison with Croton Water Treatment Plant

As AguaClara technologies extend to larger and larger cities one of the criticisms could be that the technologies are somehow limited to small scale facilities. To address this question we will compare AguaClara unit processes with one of the most recent large scale water treatment plants, the Croton Water Treatment Plant (CWTP) in NYC.

The CWTP is designed to treat 290 mgd (million gallons per day) which is equivalent to 12,700 L/s. The final cost of the project was $3.2bn. The cost per L/s of treatment capacity was thus $250,000. This is approximately 25 times more expensive than AguaClara water treatments. Of course, AguaClara water treatment plants haven’t been constructed underground in the middle of a major city! Nonetheless, the factor of 25 suggests that AguaClara technologies have a significant cost advantage.

The CWTP has 48 flocculators and 48 dissolved air flotation processes working in parallel. The flow per unit is thus 265 L/s. The current maximum size of the AguaClara Open Stacked Rapid Sand (OStaR) ilter is 20 L/s. It would be possible to design larger OStaR filters by simply including multiple sets of inlet/outlet trunk lines into a single filter box. The CWTP filters appear to have 6 outlet trunk lines per filter and thus the flow per trunk line is 44 L/s.

The CWTP uses 2 stage mechanical flocculators with a total residence time of 4.8 minutes and a velocity gradient of 100 Hz. This residence time is much shorter than conventional design requirements, about half of the residence time used by the AguaClara plants built around 2017, significantly larger than the 90 second residence time used in the AguaClara 1 L/s plants.

CWTP uses dissolved air flotation tanks that are located on top of the rapid sand filters.

The filter approach velocity (the velocity of water before it enters the sand bed) for CWTP is 4.42 mm/s. This is significantly higher than the 1.85 mm/s filtration velocity currently used in StaRS filters. StaRS filters are a stack of 6 filters and the net filtration velocity is 11 mm/s. Thus by that metric the StaRS filters are significantly smaller than the CWTP filters.

#the unit registry has been imported above and does not need to be imported again

import aguaclara

import aguaclara.core.physchem as pc

from aguaclara.core.units import unit_registry as u

Q_Croton =(290 *u.Mgal/u.day).to(u.L/u.s)

Cost_Croton = 3.2 * 10**9 * u.USD

Cost_per_Lps = Cost_Croton/Q_Croton

Cost_per_Lps

N_DAF = 48

Q_per_unit = Q_Croton/N_DAF

Q_per_unit/6

(15.9 * u.m/u.hr).to(u.mm/u.s)

Design Evolution

During the later half of the 20th century surface water treatment technologies evolved slowly. The slow evolution was likely a product of the regulatory environment, the high cost of water treatment infrastructure, and the low profit margin. The high cost of municipal scale water treatment infrastructure made experiments at scale infeasible and thus there was no mechanism to introduce disruptive innovations. With little opportunity for a significant return on investment there was little incentive to invest in the research and development that could have advanced the technologies. A final disincentive was the widely held belief that surface water treatment was a mature field with little opportunity for significant advancement. The advances of the latter half of the 20th century focused primarily on mechanization and automation (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition - SCADA).

Design standards such as the Great Lakes - Upper Mississippi River Board 10 States Standards are evolving very slowly and retain an empirical approach to design. The empirical design methodology is a direct result of two confounding factors. The physics of particle interactions based on diffusion, fluid shear, and gravity are complex and given the challenges of characterizing surface water particle suspensions it was natural to assume that a mathematical description of the processes would be intractable.

Mechanized and automated water treatment plants performed reasonably well in communities with ready access to technical support services and supply chains that could reliably deliver replacement parts. In the global south municipal water treatment plants haven’t faired as well. In 2012, one of the main water treatment plants serving Kathmandu, Nepal had failed chlorine pumps and were using a red garden hose to siphon chlorine from the stock tank. They crimped the end of the hose to control the flow rate of the chlorine solution.

Fig. 8 Failed chlorine dosing system bypassed with a red tube that siphons the chlorine solution at a plant in Kathmandu, Nepal in 2012.

The ingenious and simple chemical dosing system that uses a siphon to completely bypass the failed pumps begs the question of whether design engineers could have invented a better option than the short lived pumps that they specified. We will investigate a gravity powered chemical dosing system that is far more reliable than chemical dosing pumps and that borrows from the simplicity of the garden hose solution used by the Nepali plant operators.

Chemical dosing systems are particularly vulnerable and their failures make plant operation very challenging. Providing the right coagulant dose is critical for efficient removal of particle and dissolved organics. Chemical dosing systems commonly rely on pumps and those pumps require regular maintenance and have relatively short mean times between failures.

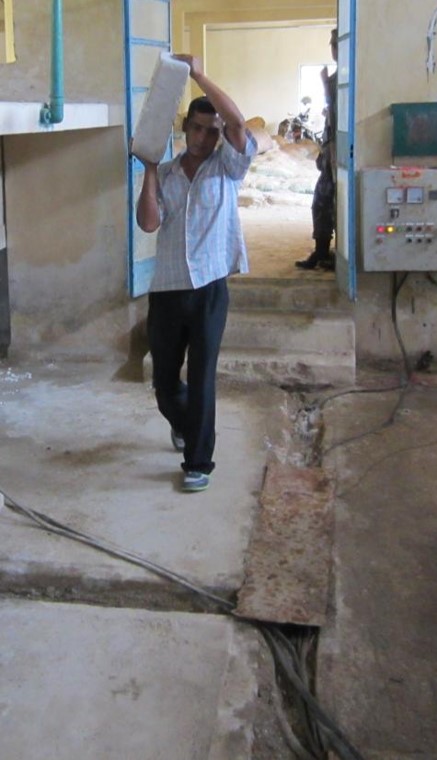

Fig. 9 Alum dosing system based on the rate that 25 kg blocks of alum are placed in the inlet channel of the plant.

The AguaClara Cornell program was founded in 2005 with the goal of creating a new generation of sustainable technologies that would perform well even in the rugged settings of rural communities. The goal wasn’t simply to create technologies that would work for communities with very limited resources. The goal was to create the next generation of technologies that would both perform well in communities with limited resources and would be the highest performing technologies on multiple metrics for all communities.

Empirical Design

For the past several decades surface water treatment technologies have been considered “mature” and when I (Monroe) took a design course on drinking water treatment in 1985 I had the impression that there was little room for further innovation. This perspective is remarkable given that with the exception of lamellar sedimentation there were no equations describing the core treatment processes.

Empirical design guidelines don’t provide insight into how designs could be optimized or even what the performance of a water treatment plant will be.

Design for the Financers, Venders, Client, or Context?

Tours of water treatment plants suggest that it is common for designs to be driven by the vender goal of a stable revenue stream for replacement parts rather than by a goal of meeting the client’s needs. Mandatory software upgrades, mechanical valves, chemical pumps, mixing units provide a steady demand for proprietary components. Financers often prefer projects that can be implemented quickly either because they have target expenditures for a fiscal year or because loan repayment begins when the facility is turned over to the client.

Design for the client would strive to reduce capital, operating, and maintenance expenses. Clients also place a high value on reliability, ease of maintenance, and the ability to handle repairs with their staff. Design for the context would account for the capabilities of local and national supply chains. A key design consideration is to ensure that the treatment capabilities of the treatment plant match the variable water quality of the proposed water source. There are numerous slow sand filtration plants installed in the global south that are attempting to treat water sources that can not be effectively treated by slow sand filtration. The cost of the failure to consider the client and the context is born by the communities who end up with water treatment systems that aren’t able to provide reliable safe water.

Design for the client requires empathy and a commitment to listen to and learn from plant operators. It also requires attention to detail and watching how plant operators interact with water treatment plants. Empathy leads to the goal of creating a work environment that makes it easy for the plant operators to do their routine tasks. This isn’t just to make the plant operators work easy. A plant that is designed with the plant operator in mind will also engender pride and that pride will lead to better plant performance.

An example of design for the operator is the elevation of the walkways in AguaClara plants. Conventional plants often have walkways that are above the tanks. That places the operator’s eyes several meters above the water surface and makes it difficult to see particles and flocs in the water. AguaClara plants have the walkways approximately 50 cm below the top of the tanks. This makes it easy for the plant operator to look into the tanks for quick visual inspections.

Fig. 10 A plant operator built a makeshift ladder to enable easier access to the flocculation and clarifiers in a package plant. This ladder considerably shortened the distance between the coagulant dose controls and the flocculator. The ladder also makes it possible to look closely at the water to see the size of the flocs.

Design Bifurcations

Seemingly small decisions can have a profound effect on the evolution of design. Often these decisions have a clear logic and a simple analysis would suggest that the decision must be the right one. It is common for design choices to have multiple consequences that can turn a seemingly great choice into a poor performer.

Walls and a Roof

Traditionally in tropical and temperate climates, flocculators and clarifiers are built without an enclosing building because they aren’t in danger of freezing. Without protection from the sun the materials used for plant construction must be UV resistant and thus plastic can’t be used. This requires use of heavier and more expensive materials such stainless steel and aluminum. Metal plate settlers are heavy and thus they can’t be easily removed by the plant operator.

Without the ability to gain access to a clarifier from above, conventional clarifier cleaning must be done by providing operator access below the plate settlers. This in turn requires that the space below the plate settlers be tall enough to accommodate a plant operator. Thus clarifiers that are built in the open have to be deeper than clarifiers that are built under a roof and they are more difficult to maintain because the operator has to enter the tank through a waterproof access port. Operator access to the space below the stainless steel or aluminum plate settlers is through a port in the side of the tank (see the video Fig. 11).

Fig. 11 Plant operators opening hatch below plate settlers in a traditional clarifier.

AguaClara clarifiers are designed to be taken off line one at a time so the water treatment plant can continue to operate during maintenance. Two plant operators can quickly open a clarifier by removing the plastic plate settlers (see the video Fig. 12). The zero settled sludge design of the AguaClara clarifiers also reduces the need for cleaning.

Fig. 12 Plant operator removing plate settlers from an AguaClara clarifier.

There is another major consequence of building water treatment plants in a secure enclosed building. Many water treatment plants will operate around the clock and that requires plant operators to spend the night at the facility. Having a secure facility provides improved safety for the plant operator. That improved safety is very important for some potential operators and thus providing that safety will increase potential diversity.

Mechanized or Smart Hydraulics

Dramatically different designs are also created when we choose gravity power and smart hydraulics rather than mechanical mixers, pumps, and mechanical controls for each of the unit processes. It appears that use of electricity in drinking water treatment plants became the popular choice about 100 years ago. Many gravity powered plants have been converted to use mechanical mixers for rapid mix and flocculation. That choice may not have been well founded from a water quality or performance perspective.

Automated plants often move the controls far away from the critical observation locations in the plant. This might be appropriate or necessary in some cases, but it has the disadvantage of making it more difficult for operators to directly observe what is happening in the plant. Direct observations are critical because even highly mechanized water treatment plants are not yet equipped with enough sensors to enable rapid troubleshooting from the control room.

AguaClara plants have a layout that places the coagulant dose controls within a few steps of the best places to observe floc formation in the flocculator. This provides plant operators with rapid feedback that is critical when the raw water changes rapidly at the beginning of a high runoff event. As operators spend time observing the processes in the plant they begin to associate cause and effect and can make operational changes to improve performance. For example, gas bubbles that carry flocs to the surface can indicate sludge accumulation in a clarifier. Rising flocs without gas bubbles can indicate a poor inlet flow distribution for a clarifier or density differences caused by temperature differences.

This is an evolving textbook. We don’t intend to ever print this book. This book has version numbers just like software with the idea that revisions are rapid and frequent. We commit to helping to accelerate the pace of knowledge generation and to revising this text as you help us identify places where we have presented hypotheses as theory and places where research provides a basis for better theoretical models of the water treatment processes.

Our students are co-creators of knowledge and not empty vessels to be filled with our wisdom. AguaClara technologies are inventions that are the result of idea collisions in the AguaClara labs and from observations and reflections with operators, technicians, and engineers in dozens of water treatment plants. Although we’ve learned a great deal about water treatment since 2005 when AguaClara was founded, there is still much more to be learned. And so it is with a spirit of curiosity that we write this textbook expecting to learn even more in the coming years.

Socrates said “Education is the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel.” Our goal is to bring the spirit of play, discovery, and mystery into the challenge of improving the quality of life of everyone on the planet by sharing better methods to produce safe drinking water.

In We Make the Road by Walking: Conversations on Education and Social Change, Paulo Freire said, “The more we become able to become a child again, to keep ourselves childlike, the more we can understand…”. We commit to playing together in a relationship where we are all learning and we are all teaching. “Education must begin with the solution of the teacher-student contradiction, by reconciling the poles of the contradiction so that both are simultaneously teachers and students.” - Paulo Freire

AguaClara Inventions

- The AguaClara treatment train consists of the following processes

flow measurement

metering of the coagulant (and chlorine) that will cause particles to stick together

mixing of the coagulant with the raw water

flocculation where the water is deformed to cause particle collisions

floc filter where large flocs settle through water that is flowing upward causing collisions between small particles carried by the upward flowing water and the large flocs

lamellar sedimentation where gravity causes particles to settle to an inclined plate and then slide back down into the floc filter

stacked rapid sand filtration where particles collide with previously deposited particles in a sand filter bed

disinfection with chlorine to inactivate any pathogens that escaped the previous unit processes

Plant layout

Compact layout with processes sharing common walls when possible

Walkways set at optimal elevation for observation and maintenance of processes

Open tanks used whenever possible to simplify maintenance

Building enclosure to protect the entire plant from UV and for security

Chemical dosing

Linear flow orifice meter to both measure the plant flow rate and to turn the entrance tank water surface into a flow sensor input for the chemical dosing system.

Gravity powered semi-automated dosing system that delivers a constant dose even when plant flow rate changes.

Slider on a calibrated scale for intuitive changes in chemical dose

Rapid mix

Simple orifice for hydraulic rapid mix or simply rely on the mixing generated by the water exiting the linear flow orifice meter.

Flocculation

Obstacles between baffles when required to create a more uniform distribution of energy dissipation rate and a more efficient use of available energy

Plastic modules that can easily be removed from channels for maintenance

Compact vertical flow flocculators for low flow plants

Floc Filter and Plate Settlers

Four channel inlet/outlet system that enables

dumping flocculated water that doesn’t meet specifications

taking one clarifier offline by placing a pipe stub in the inlet and a cap on the outlet

dumping settled water that doesn’t meet specifications

Inlet manifold with flow diffusers that straighten the flow into a continuous line jet

Inlet manifold is offset from center to force jet to all go in a consistent direction through the jet reverser

Jet reverser that efficiently reverses the direction of the incoming water to be able to resuspend settled flocs that are sliding down the inclines

Floc filter that is stable and that reduces the clarified turbidity. The floc filter coupled with the jet reverser system produces a very uniform vertical flow into the plate settlers and thus eliminates large scale flow circulation that commonly results in excess flow through some of the plate settlers.

Zero settled sludge in the main part of the clarifier

Hydraulically cleaned with no moving parts

Floc Hopper that consolidates the floc slurry prior to draining.

Filtration

Sand drain system to empty sand from filter hydraulically

Wing and orifice system to inject water into the filter bed

Stacked Rapid Sand Filtration system that has the same flow rate for filtration and for backwash

Uses settled water for backwash to eliminate need for pumps and clearwells and to eliminate failure mode of inadequate supply of filtered water for backwash.

Air valve control system to trigger mode change from backwash to filtration and from filtration to backwash

No valves needed on inlet and outlet pipes

Myths in Environmental Engineering

The following list is designed to get you thinking. These are concepts that are present in the Environmental Engineering community and that may capture some elements of truth and that may also further misconceptions.

Slow sand filters ripen (improve in ability to remove contaminants over time) because of biological growth in the filter bed

If a 20 cm deep sand filter removes 90% of influent particles, then a 40 cm deep filter will remove 99% of influent particles

If water is dirty, then you should filter it

Chlorine disinfects dirty water and makes it safe to drink

Chlorination and filtration eliminated typhoid fever from the US

Cessation of chlorination due to fear of disinfection by products caused the cholera outbreak in Peru in 1993

Clarification is simple

We already know how to solve the problem of the billions of people who do not having access to safe drinking water